이 글은 숙명여대 안보학연구소장 이민룡 교수의 논문 "북한의 제3차 핵실험 위기에서 한국과 미국의 강압회교는 성공했는가?(Coercive Diplomacy Really Worked in the Crisis of North Korea's Third Nuclear Test?)"를 요약 정리하여 게재한 것임을 알려드립니다.

2013년 2월 북한은 제3차 핵실험을 강행했다. 국제사회와 한미동맹의 경고에도 북한은 아랑곳하지 않았다. 핵실험을 저지할 방책은 과연 없었을까? 북한이 국제사회의 경고에 귀를 기울일 가능성은 없었다. 이미 유엔의 대북제재는 겹겹이 발효되었음에도 불구하고 실효성이 없었기 때문이다.

그렇다면 북한과 직접 대치하고 있는 한국과 미국이 이 위기 상황의 전면에 놓인 형국이었다. 전략적으로 한미동맹이 북한을 저지할 방책은 ‘강압외교’가 최선이었다. 북한의 핵실험 시설을 군사적으로 타격하는 방책을 생각할 수 있으나 이것은 전쟁을 불사할 각오가 있어야 가능하다.

반대로 당근책을 생각할 수 있다. 엄청난 규모의 재정적 경제적 지원을 약속하면서 핵실험을 저지하는 것이다. 이 방책은 이미 교훈을 얻은 상태이다. 경제적 지원을 하면 할수록 북한은 이 혜택을 핵무기와 미사일 개발에 활용했기 때문이다. 이런 맥락에서 ‘강압외교’가 최선의 방책이었다고 보는 것이다. 무력시위 수위를 최대한 높이면서 협상 유인책을 동시에 구사하는 전략이 바로 ‘강압외교’의 요체이다.

그런데 실제의 위기 상황에서 한국과 미국은 이 전략에 의존하였으나 강도는 그리 높지 않았다. 역으로 여러 각도에서 의문점이 발견되었다. 북한이 핵실험을 강행할 조짐이 있다는 사실을 미국정부가 공식적으로 추인하지 않았다는 사실이 첫 번째의 의문점이었다.

핵실험 시행 약 2개월 전 미국의 대학에서 핵실험 징후가 있다고 발표된 것도 의문이었다. 이로부터 공식적으로 이 사실을 확인하고 대비책 강구에 혼신의 힘을 다했던 쪽은 한국 국방부였다. 한미동맹 차원에서는 무력시위 성격의 훈련을 시행했고, 미국은 핵잠수함 1척을 출현시킨 것이 강압외교의 전부였다.

무력시위의 강도는 매우 낮았고, 미국의 위협 인식은 예상보다 낮았다. 바로 이 대목이 이 논문의 핵심 테마이다. 한미동맹 차원의 강압외교는 결국 실패했고, 북한은 핵실험을 강행한 것이다. 여기서 의문점은 새롭게 생성된다. 미국은 왜 북한 핵실험 의도를 저지하지 못했는가? 애초부터 저지할 생각이 없었던 것은 아닌가? 이미 시기적으로 늦었다고 판단하고 있는 것은 아닌가? 앞으로 북한이 4차 핵실험, 그리고 미사일 실험을 강행한다면 어떻게 될 것인가? 한미동맹은 이러한 사태에 대응할 효과적인 전략을 구비하고 있는가?

이러한 의문점들은 이 논문의 결과를 놓고 볼 때 매우 비관적인 해석을 낳게 한다. 앞으로 북한이 또 다른 핵실험을 강행할 때에도 한미동맹은 이렇다 할 전략을 구사하기 어려울 것이라는 전망이 그것이다. 미국은 국제사회와 중국의 힘을 빌리겠다는 생각에 치우쳐있다는 것이다. 한국은 북한의 위협에 더 예민한 반응을 보이겠지만 북한을 저지할 역량이 부족하다.

한국이 힘을 갖추고 있다고 하더라도 북한이 한국과 이 문제를 놓고 협상을 벌일 가능성은 매우 낮다. 그렇다면 앞으로의 위기상황에서 ‘강압외교’를 주도할 나라는 한국이며, 강압외교의 틀을 새롭게 구성하는 방식으로 추진해야 한다. 이 논문에서 제안하는 강압외교의 방식은 다국적 군대가 참여하는 강도 높은 무력시위이다.

동맹국 미국을 설득하고, 한국전쟁 참전국을 대상으로 안보외교를 펼쳐 약 20여 개국의 군대로 구성된 다국적 군사력이 북한을 굴복시키는 형식이다. 이미 북한의 전략무기 문제는 한반도와 동북아시아 지역문제를 넘어 글로벌 안보 쟁점으로 떠 오른 만큼 이러한 상황 인식에 부합되는 새로운 강압외교의 틀을 구상하고 시행에 옮겨야 할 때이다.

이민룡 교수 (숙명여대 안보학연구소장)

Lee, Min Yong (Professor and Director of Sookmyung Institute of Security Studies)

< 논문 원문 >

Coercive Diplomacy Really Worked in the Crisis of North Korea's Third Nuclear Test?

Min Yong Lee

(Sookmyung Women's university)

I. Introduction

II. Coercive Diplomacy and the Korean Peninsula

III. North Korea's Nuclear Test and Coercive Diplomacy

IV. South Korea's Strategic Options

V. Conclusion

North Korea's third nuclear test supposedly ended in a complete success in February 2013. Like previous tests, North Korea could easily secure its test attempt, with no crucial interruptions from outside world. South Korea and the U.S. joined forces to deter it, but the countermeasures they presented seemed invalid and unrealistic. This is to mean that they failed to coerce North Korea not to conduct a nuclear test. This point is our main

research question as to why the coercing countries could not able to stop North Korea. Based upon the strategy of coercive diplomacy, we identify three policy requirements for the pursuit of coercive diplomacy in the first place, and apply them to evaluate the coercers' performance in preventing North Korea from prosecuting a nuclear test.

Eventually, we found that the coercers did not do their best efforts to fulfill the minimum requirements for coercive diplomacy. In the last part, we suggest policy recommendations to South Korea, on the premise of its opt for coercive diplomacy.

Our utmost recommendation is that South Korea readily call for coalition forces to counter North Korea's further aggression. Key words; coercive diplomacy, a nuclear test, deterrence and compellence, military coercion, UN sanctions, crisis, preventive strik.

I. Introduction

North Korea conducted a nuclear test again in February 2013, its third in seven years. This test has presumably helped change the North Korea's political position to become a new nuclear power state.

According to a Russian media source, North Korea announced that the test had used a miniaturized nuclear device with greater explosive power.1) If true, North Korea should be struggling with more outside pressures since international norms and vested nuclear powers stand to block a new entry to the status of nuclear powers.

Even China, a sole and brotherhood ally of North Korea, has been fiddling with a red card.

Headed by the United Nations, the international society has condemned North Korea's nuclear tests, establishing a series of sanctions that have revealed unproven effects yet.2) Experts occasionally see the sanctions work because North Korea has been reluctant to step further since its third test.3) Sanctions by the United Nations, however, have not been so fruitful in general terms. Some of them might work well at times, but much patience and endurance follows behind success.

Especially, it is much more demanding to put pressure by sanctions against such a outcast like North Korea, because it has been good at withstanding outside challenges by tightening its domestic autonomous mechanism established by a tough self-reliant economic system.

It is against this backdrop that the strategy of coercive diplomacy must be an alternative option in coping with North Korea's attempts for strategic weapons like nuclear bombs. In fact, North Korea had continued the tests for missile and nuclear weapons before the third nuclear test,without respect to United Nations' sanctions.

This is to prove that international sanctions are also unfruitful in the Korean peninsula, and

consequently we need to investigate other strategic options for the defensive countries like South Korea and the U.S. The two countries have been committed and responsible actors in confronting with North Korea in major security problems including nuclear weapon issues.

From this standpoint, they deserved to be blamed for the failure of deterring the North Korea's third nuclear test, because they actually undertook counter-actions against North Korea's threat.

However, it might be overstated to say that South Korea and the U.S. together are fully

capable of managing North Korea's provocative stance. Over the years, North Korea has revealed its firm willingness to capture the status of a nuclear power. Such a tough offensive position naturally let the coercers in a vulnerable position in crisis situations.

For the coercers, an active interruption like a surgical attack of nuclear facilities would certainly trigger the danger of a total war bringing nuclear casualties in the whole Northeast Asia. By contrast, appeasement strategies like diplomatic and bargaining options would help promote North Korea's nuclear programs. Consequently, the coercers have no choice but to rely on the strategy of coercive diplomacy.

This strategy is presumably a realistic or plausible option for the coercers, especially in countering North Korea's provocations. Concentrating upon coercive diplomacy, this paper aims at investigating the response procedure that South Korea and the U.S. executed on the verge of North Korea's third nuclear test. To this end, we suggest three research questions: to probe and manipulate factors favoring the success of coercive diplomacy in the context of the Korean peninsula; to evaluate South Korea-the U.S. responding policy actions;

to suggest key policy recommendations for South Korea to pursue coercive diplomacy against North Korea.

II. Coercive Diplomacy and the Korean Peninsula

1) Coercive Diplomacy and Crisis Management

Coercive diplomacy is a bargaining strategy to persuade an opponent to stop any further actions in international crisis situations. In the coercing process, carrots are occasionally used, but mostly sticks become a main instrument. Alexander George, a towering figure who

made numerous pioneering and enduring contributions in international crisis studies, defines coercive diplomacy as a political-diplomatic strategy that aims to induce an adversary to comply with one's demands, or to negotiate the most favorable compromise possible, while

simultaneously managing the crisis to prevent unwanted military escalation.4)

Coercive diplomacy is based on the anti-war tradition seeking compromise at stake. For the coercer's part, military force becomes a core instrument, and its role is not to trigger a war or an armed clash, but only to threaten the target state. This tradition differs from deterrence and compellence. Deterrence invokes threats to dissuade an adversary from initiating an undesired action, whereas coercive diplomacy is a response to an action that has already been taken.5)

Meanwhile, coercive diplomacy is also different from military compellence in the sense that it may include positive inducements and accommodation along with military coercion. Military compellence is an offensive strategy actualizing the use of military force, but coercive

diplomacy is a defensive strategy pressing an adversary not to breakaway from the status quo.6)

The coercer is expected to create the opportunities to talks and bargaining towards the target. In the initial stage, the coercer has to threaten the target by military force to yield any further aggression. At the same time, it needs to allure the target with inducements for a

bargaining position. In the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, for example, the Kennedy

administration won the success by employing coercive diplomacy against the Khrushchev regime.

Having enforced a tough naval blockade to Cuba, the U.S. also proposed to remove the strategic missiles deployed in Turkey. The Panmunjom crisis of 1976, so-called

"the Axe murder incident", is also cited as a successful coercive diplomacy by the U.S.. Then US President Gerald Ford decided to execute a military operation, the demonstration of power cutting down the tree with the aid of overwhelming force, but without causing further

escalation.

The operation "Paul Bunyan" was carried out without any resistance from North Korea. The crisis was not developed into a more intense armed confrontations, although the U.S. did not suggest any inducements to North Korea. This case represents a good example for the coercer to realize its objective by demonstrating military power only, without any concurrent inducements.

Coercive diplomacy is enough to capture policy makers' attention, because of its innate advantage as a strategy of international crisis management. It is not without risks though. Both states at stake are likely swayed into an unwanted armed clashes, when the target country disregards military intimidation from the coercer.

This scenario appears when the coercer fails to use credible military forces, and the target is incompetent to recognize threat itself. In the early 1965, the U.S. had bombed the Hanoi as a way to prevent North Vietnam from launching a preemptive strike, but this operation was interpreted as a kind of blackmail.

North Vietnamese leaders saw it unlikely that the U.S. intended to involve in an all-out war in Vietnam. Together with a clumsy stance from the U.S. and the misperception from North Vietnam, it proves that coercive diplomacy, in the worst case, would bring a more intense warfare.

With this risk in mind, scholars and experts have payed strenuous efforts to find the primary factors favoring the success of coercive diplomacy.7) Eventually, it turns out that pinpointing a few sensible factors is meaningless, because coercive diplomacy is highly context

dependent. Recognizing this problem, we find it more reasonable to concentrate upon identifying basic requirements that the coercer should meet when prosecuting the strategy of coercive diplomacy.

Previous studies suggest numerous candidates, of which we pick ones with most references. In the end, we have identified three requirements: to manipulate and send a clear message to the target; to put pressure by military coercion; and to propose adequate inducements for bargaining.

These requirements are not considered either necessary or sufficient conditions for the success of coercive diplomacy, because other complex and various factors work variably in reality. Instead, we argue that three requirements could rather be treated as least minimum conditions for the coercer to work out the strategy of coercive diplomacy.

First, the coercer's demand must be clearly understood by the target. To that end, the coercer needs to clarify its objectives and to seek for the ordinary stakes associated with the call for merely policy change. This is to limit the coercer's demand to the level that the target easily complies with. The problem arises when the coercer demands the call for the regime change or political transitions in the target state beyond policy change.8) Such an excessive demand would drive the target state into a blind alley to take more intense aggression.

Consequently, the coercer must articulate the specific conditions to resolve the crisis, as well as to give assurances not to formulate additional demand for further concessions once the target capitulates. Timing is also important. The coercer needs to deliver its demand prior to the target making a firm commitment on the issue at hand.

Second, the coercer must demonstrate the threat of force to issue a warning and gradually increase pressure on the target. The end state is to assure the target to convince that accommodating to demands will be better than defying them. Traditionally the strong powers have relied on various methods dispatching their gunboats or displaying cutting-edge

smart weapons.

By all means, the coercer has to hold its capability to increase pressure to the level that the target would find intolerable. In the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, President Kennedy posed coercive threats by military actions at the onset of the crisis in order to show off his own credibility and reverse any image of weakness in the mind of the adversary, even though he was quite willing to be conciliatory toward Khrushchev.9) As Alexander George strongly argues, a purely diplomatic strategy without coercive threats would have been more likely

to escalate to risky military action.10)

The point is how smart the coercer can be in articulating coercive threats by means of military and economic power. Third, the coercer must be able to assure the target to recognize a

bargaining position in case the target would comply with the coercer's demand. This involves an explicit or at least mutually tacit understanding of a deal between the coercer's carrots and the target's concessions.11)

As long as the coercer's main objective is to win an immediate crisis situation, it must show a firm resolution by all means. It is no doubt that military force is essential to get the coercer a determined stance. However, the heavy reliance on sticks only is likely to capture the

target with a blackmail, letting the target choose 'a wait-and-see' strategy.

In this context, suggesting positive inducements can provide both sides with a renovative position introducing "something for something" rather than "nothing for something". Carrots would also help the target find an honorable exit plan from a crisis, preserving political

leadership circumstantially.

Likewise, carrots would allow the coercer to reinforce its resolute stance, because the target will recognize a sincerity and urgency from the coercer's full range of operations. 2) Coercive Diplomacy in the Korean peninsula Great powers are easily captured by coercive diplomacy, but various factors set conditions for its success.

However elaborative policy options are, the coercer would unavoidably encounter hurdles especially when the target is inherently inadvertent or abnormal. Over the years, South Korea and the U.S. have kept common steps to deter North Korea's attempts for nuclear

development. They executed strategies like coercive diplomacy whenever North Korea demonstrated its willingness for nuclear tests, but no fruitful results appeared yet.

Presumably, this is because North Korea is abnormal, as usually called 'a rogue state'. Such an outsider disposition normally refuses to admit any rational choices requested from international actors. Or it might be immovable because it predetermined the status of a nuclear power as an end state in its grand national strategy.

Either way, South Korea and the U.S. should inevitably meet fundamental obstacles in articulating and implementing counter actions. To make matters worse, the two countries have no choice but to rely on coercive diplomacy. Depending on military compellence, a choice preoccupied by the use of military forces, can not be treated as rational because it is highly likely to introduce a full-scale war in the Korean peninsula and its environs as well.

By contrast, relying on a bargaining strategy only, as shown in the six-party talks, has proved to easily allow North Korea a chance to promote its nuclear programs confidentially. On the premise that either extreme way is far from desirable and plausible, ruling politicians and policy makers of South Korea and the U.S. have held on to the strategy of coercive diplomacy as the only and last measure. As a first priority, this strategy secures attention by its two track approach applying sticks and carrots simultaneously.

Especially for the coercer, in the absence of a clear-cut solution at the critical moment of a crisis, it is supposed that a combination of sticks and carrots at the high rate of sticks could be a most probable cause of action. Specific rate of combination is highly context dependent, with a function of the nature of crisis, actors' perception of war, the degree of

time urgency, and so forth.

In the Korean peninsula, North Korea has long wanted a target state position, throughout undertaking numerous provocations, while South Korea and its military ally the U.S. have maintained a coercer's position to deter further aggression. Focusing on this security structure in the Korean peninsula, we articulate policy options or conducts for the coercer in pursuing the strategy of coercive diplomacy, especially regarding of North Korea's aggression on the development of nuclear weapons.

① Formulating and sending objectives; demand must be specific and

clear, being limited in scope, but decisive to get the target pressed by

urgency.

▪ Concentrating upon only the cancel of a nuclear test; restraining

from demanding the abandonment of a nuclear state position, or regime

change.

▪ Demonstrating the determined willingness not to permit a nuclear

test; compelling North Korea to recognize that any nuclear test must be

intolerable to neighboring states and international society as well.

▪ Delivering time urgency; sending a warning to pursue more intense

and crucial actions after North Korea's prosecution of a nuclear test.

② Demonstrating the threat of force; military force should be mobilized

to the level that exploits the target's fears of escalation to war.

▪ Blockading; shutting out all passage ways of North Korea's territorial

facilities by cutting-edge missiles or fighters

▪ Dispatching aircraft carriers; launching aircraft carriers to the Korean

peninsula

▪ Executing military exercises; starting a full-scale military exercise by

the ally forces

▪ Alerting military readiness; declaring the state of combat readiness

to get involved in a full-scale war

▪ Demonstrating new military weapons or equipments; making a

disclosure of the latest fearful weapons or arms to enforce preemptive

strikes

③ Implying concessions; adequate inducements should be prepared

explicitly or tacitly in return for the target's comply.

▪ Promising a large scale economic assistance; suggesting assistance

programs for energy, food, and other economic supports in exchange for

North Korea's cancel of a nuclear test

▪ Expressing a willingness for dialogues; signalling a readiness to

reopen any dialogue channels including the non-nuclearization of the

Korean peninsula

III. North Korea's Nuclear Test and Coercive Diplomacy

1) Prelude of Crisis

On 12 February 2013, a North Korea's army spokesman officially announced that North Korea had conducted a third underground nuclear weapon test. He also added that the test had used a miniaturized nuclear device with greater explosive power.

International agencies confirmed a tremor from North Korean territory, exhibiting a nuclear bomb signature.12) This was not the end however. A symptom for further tests was reported from various sources. The following day, a South Korean military official stated, after investigating nuclear facilities, that North Korea would probably conduct another test.13)

It was also reported on February 15 that North Korea had informed China that they were

preparing for more nuclear tests. A U.S. agency also confirmed that North Korea was already set to conduct another test but hesitating due to the fear that it would anger China.14)

North Korea's drastic enforcement of the third nuclear test proves that the Kim Jong-eun regime, the successor of his farther Kim Jong-il, has succeeded to the legacy of "the Strong and Prosperous Country" (Gannsung Daeguk in Korean).

Kim Jong-eun was crowned the supreme leader by the early 2012, no less than two months after his farther's death, monopolizing main power positions in the party, military, and other state organizations. Shortly after that, he decided to launch a rocket called "Unha-3" on April 13 but it exploded in 90 seconds after launch. On 12 December 2012, North Korea launched another rocket, and this time it announced that the test was successful.

Consequently, the third nuclear test was a signal to prove that the new North Korea regime has no intention to give up its strategic programs aiming at the status of a nuclear power.

Interestingly and surprisingly enough, it was an U.S. expert named Nick Hansen, an affiliate of the Center for International Security and Cooperation at the Stanford University, to first detect and release an evidence of North Korea's movement for nuclear test. On 7 December

2012, he exposed, after analyzing satellite pictures, that North Korea was getting closer to the stage of a nuclear test.15)

Another report was released on December 28 by the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins

University, indicating that North Korea would be at the ready for a third nuclear test once it fixed nuclear facilities from flood damage.16) It was South Korea's Ministry of Defense to first recognize and confirm a nuclear test symptom from North Korea, but no official response was released from the U.S. government. On December 12, South Korea defense minister Kim Kwan Jin admitted, in the National Defense Commission at the National Assembly, that North Korea was on the verge of a nuclear test, only being a matter of political decision.

The following day, the South Korea government spokesman reaffirmed North Korea at the ready for a nuclear test, referring that it completed the restoration of nuclear facilities.17) To be sure, the South Korean government grasped an unusual nuclear movement from North Koreas, at least 50 days prior to the actual carry-out of the third nuclear test.

No more evidence was necessary because North Korea officially announced on December 24, through the National Defense Commission citing the supreme leader Kim Jong-eun's determination, that they were willing to conduct a nuclear test. Consequently, South Korea and the U.S. were put on red alert. Once again, the South Korea Ministry of Defense saw another crisis imminent and reminded of its full readiness to keep the suspected locations under constant surveillance.

On December 28, the spokesman of the Chinese foreign ministry also expressed a deep concern of North Korea's nuclear movements,indicating an untolerable position. When considering North Korea's forewarning and the prior notice by U.S. experts, it wonders why the U.S. government and international agencies maintained a passive stance on this crisis development.

South Korea was a most active country in facing North Korea's provocative movement. It is true that China showed a way different position toward North Korea, but it remained mere talk of worries reluctantly.

Fundamentally, this unusual development must be considered an urgent crisis, but actually it was not developed to that level, only remaining at a tension-ridden moment. Although the U.S. was a most responsible and strong power, it rather wanted a back-up position in the new crisis development.

2) Coercive Diplomacy against North Korea

① Establishing Objectives

It was the late January 2013 that South Korea expressed its first official message to North Korea. This response was too late because it appeared in almost 50 days later from the first detect of North Korea's nuclear test movements. On 29 January 2013, the spokesman of South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanded North Korea to abandon its nuclear test plan, also accusing other weapon programs of mass destruction.

The U.S. had already expressed its official response a few days ahead, but it was too vague and elusive. Glen Davis, the special representative of the U.S. policy toward North Korea, told reporters in Seoul on January 24 that the U.S. would be willing to talk on the promise of North Korea's abandonment of WMD programs. When considering the two countries' initial responses, it seems quite clear that they were not well prepared for the strategy of coercive diplomacy.

Unfortunately, they waisted so valuable time in vain until the official pronounce of a first message. They should have expressed it much earlier instead, as soon as they detected a nuclear test movement. On the other hand, the messages that the two countries formulated should have been more clearer and acceptable, demanding only the abandonment of a nuclear test.

What actually they demanded was the full shut down of all WMD programs. Consequently, South Korea and the U.S. looked incompetent to capture North Korea in the state of urgency and the lure of negotiation. For North Korea, this demand was neither

acceptable nor negotiable on any account.

Thereafter, South Korea continued strenuous efforts to show off its determined will, focusing on diplomatic and military coercion, but they were mostly the day after the fair.Diplomatically, South Korea requested an additional sanction by United Nations and appealed to international

public sentiment.

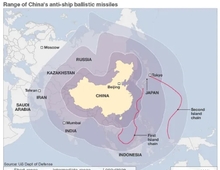

This coercion was useless because North Korea had already been met with international sanctions and a harsh condemnation worldwide as put by "a rogue state". Likewise, South Korea signalled to opt for military coercion, expressing its willingness to deploy new ballistic missiles with a range of 800 Km, and to revise its military strategy to conduct preemptive strikes.

These options also seemed unavailing because South Korea was not well equipped with militarycapability to undertake such an offensive operation. It is no doubt that the U.S. was a competent state, but it did not move on the enforcement of a strong military coercion.

With the support from the U.S., South Korea should have put pressure more tightly. In formulating message, South Korea could have signalled its firm resolution, indicating catastrophic side-effects by nuclear tests, and urging domestic and worldwide uprisings against nuclear provocation. At the same time, it should have helped promote anti-nuclear protests domestically, and appeal to great powers and United Nations for more intensive engagement.

South Korea, as it has been always so, failed to give salience to nuclear danger and to remind the fact that nuclear provocation would be an inexcusable challenge for the whole Korean nation and the northeast Asia as well. China turned to the position of the coercer, blaming North Korea.

On January 30, the spokesman of Chinese Foreign Ministry recommended North Korea not to conduct any further nuclear test, making an additional demand for neighbouring states to keep their head. This kind of cool response from China was unusual indeed, because it had used to automatically take part with North Korea in any occasions of security

affairs.

By delivering a kind of warning to North Korea, China showed a determined will not to admit any further deterioration of nuclear danger in the Korean peninsula. However, the China factor couldn't get its momentum as the Chinese government also requested South Korea and

the U.S. to fulfill corresponding efforts.

As for multilateral efforts, a joint statement was presented in Tokyo on January 31 among South Korea, the U.S., and Japan. In the assistant secretary level talk, the countries warned North Korea that the conduct of a nuclear test would bring international censure and additional sanctions.

They also referred to the danger of North Korea's test firing of missiles. Such a multilateral response was timely and necessary but it did not seem to work well to prevent the impending nuclear crisis,because the coercers' demand was too ambitious and indefinite,requesting the complete abandonment of WMD programs. That was certainly unacceptable to North Korea. Again, the coercing states should have focused only upon calling North Korea to stop or suspend its nuclear test program.

As evidence mounted that a nuclear test was imminent, South Korea and the U.S. decided to take a common step to send a warning message. After a phone call requested by the U.S. side on February 3, both foreign ministers reaffirmed their shared will to sternly counter against any provocations from North Korea.

On February 8, just four days before the conduct of a nuclear test, the defense ministers of both countries also expressed their firm determination to prepare military countermeasures against North Korea's conduct of a nuclear test.

However, such a response became a mear verbal warning, because it was not only an ad-hoc compromise resulted from a phone call exchange, but also just like a day after the fair concentrating upon follow-up tasks. Instead, the two countries should have presented a

presidential level communique to demonstrate their firm resolution.

It wonders why the U.S. maintained a passive stance in facing such a crucial crisis situation. At the first sight, the U.S. seemed to undertake a strategy of coercive diplomacy, but actually it rather seemed to entrust the matter to China, just with a minimal expectation from South Korea.

In fact, U.S. high-level officials including the Secretary of State Hillary Clinton presented statements putting seemingly in trust with China's willing engagement in North Korea's nuclear problem.18) This is to prove,

on the premise of China's engagement, that the U.S. couldn't help but take an evasive stance. This might be misleading because China's engagement was vulnerable or marginal from the outset when considering the predestined relations of China and North Korea. We may possibly recognize China holding a whip against North Korea, but hardly see it whacking its ally. Consequently, the U.S. was hardly free from criticism of letting North Korea go on the nuclear test plan.

② Demonstrating Military Power

With the deliverance of warnings, South Korea and the U.S. undertook various military options that mostly belonged to a low level coercion involving the execution of combined training exercises and the demonstration of high-tech arsenals. Again, South Korea took the lead in

this task, while the U.S. seemingly wanted to act as a guardian.

With the passive stance from the U.S., the strategy of coercive diplomacy was to meet its doom. To be sure, no proper assurance was provided to capture North Korea into the fear of war. Presumably, South Korea could replace the U.S. in enforcing military coercion, but it had neither a finishing military blow nor adequate offensive weapons to conduct retaliatory strikes.

It was early February, about a week before the third nuclear test, that South Korea

demonstrated its first action for military coercion. South Korea and the U.S. together executed a large scale naval combat exercise for the February 4-6 period. In this training, a U.S. nuclear submarine and South Korea's cutting-edge destroyers 'Aegis' showed off

as a way to coerce North Korea.

South Korea continued its independent naval exercise as of February 8, right after the end of the combined exercise. However, this coercion seemed to fail in gaining its efficacy, because it was not a contingency counter-action but a premeditated one.

The two countries reportedly decided to upgrade training intensity in order to deter North Korea's provocation. This reaction was not enough because the demonstration of military power must be like a flash of lightening and overawed enough to intimidate the target country. The actual conduct that South Korea and the U.S. demonstrated obviously fell

short of such expectation.

South Korea chose a few military measures that seemed coercive actions before this naval exercise. On 13 December 2012, the South Korea Defense Ministry confirmed its plan to establish an anti-missile system called 'Kill Chain', shifting one or two years ahead of 2015. On December 31, the defense minister Kim Kwan-jin was known to give direction to develop and deploy 800Km-class ballistic missiles. This missile program had been supposed to appear in the field starting from 2017, but it was advanced by a few years because of North Korea's nuclear test movement.

These two announcements, however, were too premeditated and doubted to become feasible options for the military coercion. For South Korea, seeking certain military options was timely

necessary when considering North Korea's preparedness for a nuclear test, but the options that it actually chose looked way far from coercing North Korea.

The U.S. attempted a testing fire of anti-missile strikes as a way to demonstrate its military readiness against North Korea. On 27 January 2013, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that the testing fire had been successfully conducted in the California coast. In the absence of the government approval, experts saw this testing fire as a demonstration of military power against North Korea and Iran, the countries developing WMDs.

Presumably, this show-off could be a most effective demonstration to threaten North Korea to halt its missile test, but it could also become an instrument to counter against nuclear weapons in the long-term prospect, because North Korea's nuclear test aimed at miniaturizing its nuclear war heads to be loaded in missiles.

Much to our regret, however, the U.S. did not express its strong willingness to undertake a preemptive strike against North Korea's nuclear provocation. North Korea was probably well attentive to the U.S. announcement, but it might surely be relaxed at the U.S. posture less

probable to take an interception strike.

Korea and the U.S. revealed their shared belief to establish the strategy of preemptive strike under condition that North Korea would carry out a nuclear test. On 4 February 2013, a South Korean defense official confirmed that the two countries agreed upon the tailored counter

strategy against North Korea's nuclear threats. Again, this warning looked inadequate to become an instrument of coercion, on the grounds that it only came up with a

countermeasure.

Unfortunately, more effective and realistic military coercion was presented as soon as North Korea went through its nuclear test. The spokesman of South Korea Ministry of Defense declared in the next day after the nuclear test, that his country had already deployed 500Km

class missiles, ship-to-surface and submarine-to-surface, to undertake counter-attack against North Korea's nuclear threat. On February 14, two days after the nuclear test, Defense Minister Kim Kwan-jin also reaffirmed an immediate retaliation by missiles to any aggressions by North Korea.

His statement was presented shortly after the South Korea's naval forces had demonstrated

its missile launching, presumably aimed to strike strategic targets within North Korean territory. Additionally, South Korea began large scale military exercises to counter against any likely provocations after the third nuclear test. Naval forces prosecuted maritime action drills in the both east and west sea from February 13 to 16. South Korea-U.S. air forces also conducted wartime operational drills from February 12 to 15.

In the end, no further provocation appeared from North Korea, and the crisis came to a close in the Korean peninsula. However, North Korea gained as much as it wished throughout the crisis, while South Korea and the U.S. as the coercer couldn't manage to avoid the crisis.

Questions regarding the coercer's failure remain to be answered, but it is an undeniable fact that the coercer fell short of enforcing military coercion to resist the target's venture for crisis.

③ Suggesting Bargaining Chips

For the coercer, allurement could help promote its standing position vis-a-vis the target, producing a conciliatory phase on the verge of crisis. In fact, South Korea and the U.S. did not prepare for any decoys to lure North Korea to pause for a moment, only acting under coercion.

South Korea, a leading coercer in the crisis, run through the warnings to admonish North Korean leaders; to turn to economic regeneration, to give up any further provocations, and to bend an ear to international opinion. This message, however, would result in a reverse effect,

because it sounded like an interference in domestic affairs to North Korea. Instead, South Korea should have delivered a conciliatory message to fiddle with benefits in return for the abandonment of crisis.

For example, South Korea could offer economic assistance programs or security talks, asking North Korea to abandon its nuclear test plan. On the other hand, China was exceptionally stern in facing its ally's adventurism, but it also focused upon the coercion, warning crucially of up-coming international sanctions following after the prosecution of a

nuclear test.

Opposition opinion was dominant within China, blaming North Korea. Apart from any appeasements, domestic opinion recommended the government to reduce economic assistance toward North Korea.19) For North Korea, China's warning would surely sound

alarming because China was a sole and final life-line for its economy. Again, China gave no significant appeasement to which its ally could listen.

The U.S. was a most prominent actor for both coercion and appeasement, but it was actually reluctant in wielding both. The formal demand that the U.S. requested to North Korea was the abandonment of the whole programs of missile and nuclear weapons. This offer was so

comprehensive and vague that North Korea could hardly accept it as a compromise. As for the crisis termination, the U.S. reiterated the statement that North Korea should not make a mistake.

It seems clear that the U.S. expected China's role of arbitration this time, but this wait-and-see approach turned out to be unfruitful after all. From the coercive diplomacy point of view, most regretable was the absence of appeasement measures to allure North Korea. The reason for that was somehow for certain when considering the background of security environment.

It was just immediately after North Korea's test launch of missile on 12 December 2012 that the coercer countries also detected North Korea's movement for a nuclear test. Under such an acute tension, the coercers could not but choose compellence rather than appeasement. However, the coercers were not free from criticism, since they were not even good at employing military coercion.

3) Evaluating Coercive Diplomacy

When assuming their primary and responsible status in facing North Korea's attempt for a nuclear test, South Korea and the U.S. failed to carry out the task requirements for coercive diplomacy. From our analysis, we can identify a few reasons for the failure. First, both

countries did not show firm resolution to conduct the strategy of coercive diplomacy.

The U.S. constantly looked on with folded arms,maintaining a cursory gesture for coercion. South Korea was tougher than its ally, but it lacked substantial leverage to become a real coercer. Second, China voluntarily participated in the coercer's position, but its stance was dubious, persuading simultaneously both its ally not to go ahead of a nuclear test and the coercers not to intensify the crisis.

China's ambiguous position was not so helpful in the execution of the strategy of coercive diplomacy. Third, the coercers did not prepare adequate appeasements at all, only concentrating upon coercion. To be sure, North Korea was so reckless in attempting for strategic weapons that any appeasements from the coercers could hardly be acceptable.

Nonetheless, the coercing countries would rather prepare a decoy to induce the target in any desperate circumstances. In that sense, the coercers did not seem well adaptive to coercive diplomacy.

For North Korea, transforming the crisis into a more intensified phase would probably become its intended objective. It is true that such an impending crisis is more likely to trigger military clashes, but a hostile country like North Korea has been more familiar with the practice

employing crisis situations as an instrument for diplomacy.

Once North Korea created the nuclear crisis by its own phase, its adversaries would naturally demonstrate stronger reactions, consequently resulting in a more acute confrontation. North Korea might believe that the more intensified the crisis the more inducive the bargaining.

As the international society and its adversaries had tightened their sanctions,blocking any possibilities for negotiations, North Korea couldn't help conducting aggressions as a way to draw attentions from outside world. With no signal to get the crisis worse, North Korea could find no other choice but to carry out its nuclear test plan. From this standpoint, North Korea must have been disappointed with the coercing countries adhered to a too cautious stance.

IV. South Korea's Strategic Options

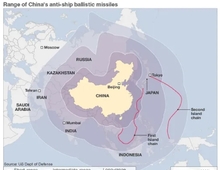

It is no doubt that North Korea has already become a tacit nuclear power holding nuclear warhead. North Korea officially confirmed it on 10 February 2005, and questions have been centered around what quality level its nuclear weapons belong to. Over the years, North Korea carried out its nuclear test programs, and outside countries have estimated their purpose being focused upon improving a miniaturized nuclear device with greater explosive power.

On the assumption that the tests were successful, North Korea could be able to adequately load nuclear warhead into its strategic missiles that were also improved ambitiously over the years.

South Korea, already within North Korea's short and intermediate range missile shots, faces a crucial stage in strategic and tactical levels.Strategically, it has to overcome the disadvantage resulting from North Korea's rise in political positions in the East Asia and the whole world as well. North Korea would take on the U.S. by exploiting its nuclear power status, excluding South Korea in any bargaining tables.

Then, the South Korea-U.S. alliance would meet severe turbulence, reaching a worst-case scenario, a nightmare for South Koreans to see U.S. forces withdrawing from the Korean peninsula. Tactically, South Korea has to conquer nuclear weapon threats from North Korea in the state of war.

Realistically, it can't help but rely on its ally's nuclear umbrella, but this policy is nothing but a last resort because both parties at usage of nuclear weapons must risk co-destruction in the end. Obviously and reasonably, South Korea has to pick the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula as the primacy of security policy. To that end, it has to take two tasks under consideration.

First, South Korea should seek the state of balance of terror in the Korean peninsula. This task can be accomplished by the reinforcement of South Korea's nuclear deterrence capability, after all implying the devise of a more reliable measure to extend the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The main purpose is to assure North Korea to recognize South Korean territory

within the deployment of nuclear weapons.

For South Korea, seeking the balance of terror in the Korean peninsula is only a process task rather than an end state. Presumably, both Koreas would easily encounter a bargaining stage for denuclearization in the culmination of nuclear danger.

This expectation compels South Korea to rely on U.S. nuclear weapons provisionally, since an access to develop nuclear weapons is not a plausible and desirable choice. Second, South Korea has to improve its own deterrence capability.

Apart from nuclear capability, it should be able to upgrade precision-guided missiles or munitions. The purpose aims to strike strategic targets. In emergency, it would help South Korea venture a preventive strike against North Korea's nuclear or missile sites.

In fact, South Korea's naval and air force combat readiness is overwhelming, and

even its short range missiles can attack any strategic targets within North Korea once precision-guided system is well improved.

As for coercive diplomacy, South Korea is not in position to pursue it as a coping strategy against North Korea's provocation. It lacks substantial military power as yet, not to mention of retaliation capability. As long as the South Korea's operational commanding right is

committed to the U.S. forces, North Korea will discount the credibility of South Korea's retaliation. Moreover, South Korea's unilateral and unconditional pursuit of appeasement policies over the last decade turned out to be unfruitful by North Korea's reckless provocations.

This is to certify that additional appeasements are not easily acceptable to South Korea, consequently weakening its bargaining power vis-a-vis North Korea. Indeed, South Korea has no autonomous and core competence to implement the strategy of coercive diplomacy. However, it can not disregard or avoid the strategy because no other resonable options can

be replaceable at the moment.

More compellence may cause the endurance of a cold war like confrontation, while more appeasement may allow North Korea's gradual improvements for strategic weapons. It is

inevitable for South Korea, therefore, to maintain the strategy of coercive diplomacy in order to prevent North Korea from undertaking provocations. In so doing, it needs to revise the conduct manuals for the pursuit of coercive diplomacy.

First, South Korea has to identify ways to increase its credibility for retaliation. It has to set limits to the impending crisis, not to the whole strategic target. Up until now, South Korea failed to stop any one of provocations attempted by North Korea. Meanwhile, North Korea

gradually moved to its end state aiming at the state of nuclear power, by occasionally provoking a crisis on its own terms.

This is to mean that if South Korea let every crisis go as North Korea wants, then it

will eventually allow its adversary to realize an intermediate goal. For this reason, South Korea should focus upon the resolution of a crisis,never allowing North Korea to take advantage of crisis provocations. In so doing, it needs to concentrate social and military potentials to

enhance its credibility for retaliation.

An all-out war posture must be demonstrated in various national fronts. Diplomatically, South Korea may suggest major powers to actively engage in crisis resolution. Of course, China is a key target country because of its predestined political leverage toward North Korea.

Second, military coercion must be demonstrated more intensively.

South Korea may request its ally to send more combat forces in crisis situations, and additionally it has to pursue a new project to call for the ad-hoc establishment of a multinational forces. To that end, South Korea could seek for a resolution of the UN Security Council in the first place, but it could also carry into action without it, requesting various countries to join an ad-hoc forces to counter North Korea's further nuclear movements. It is no doubt that the U.S. has its own military power enough to enforce military coercion in the Korean peninsula.

However, the security dynamics of the Korean peninsula is so sensitive and complicated that even hegemonic powers like the U.S. are not easily capable of driving military coercion. Accordingly, South Korea has to gain initiative in calling for a multinational forces, inviting surrounding powers like China, Japan, Russia, and other outside countries.

Third, South Korea should continue to identify appeasements to induce North Korea to bargaining tables. Previous achievements that the two Koreas built up during the last reconciliation period are so valuable to revive South Korea's leverage over North Korea. However, any assumed appeasements must be prosecuted together with military coercion.

Such a cautious position is an utmost requirement to prevent North Korea from converting economic assistances into the improvement of strategic weapons.

V . Conclusion

This paper has suggested research questions concerning the performance of coercive diplomacy in the crisis of the third nuclear test by North Korea. In the first question, we have attempted to identify certain policy requirements for coercive diplomacy that can be applicable to the context of the Korean peninsula.

Eventually, we have reached to suggest at least three minimum requisites necessary for the coercer; proposing clear objectives, demonstrating military power, and preparing

concession. In facing North Korea's attempt for a nuclear test in February 2013, the coercers engaged in performing coercive diplomacy, but eventually they failed to deter North Korea from executing the test.

It was an eye-opening progress that China turned to the coercer's position, coming off the traditional friendship with North Korea. With the help from China, South Korea and the U.S. seemed to try their utmost for coercion. However, our analysis found that the coercers did not do their best efforts to fulfill the minimum requirements for coercive diplomacy.

The objective that they wished in sending messages were too broad or ambiguous to threaten North Korea, while the military coercion was restricted to the execution of a contingent military exercise by the South Korea-U.S. allied forces and the display of precision-guided missile launching by South Korea.

The U.S. was lukewarm in joining the drill, displaying a nuclear-powered submarine as an intimidating power. No aircraft carrier or additional forces were dispatched in the Korean

peninsula. China did not show any military coercions, depending only upon verbal warnings. Moreover, the coercers did not prepare adequate concessions to move North Korea into a bargaining position.

Lastly, we have suggested policy recommendations to South Korea, on the premise of its opt for coercive diplomacy. Overbearingly, we strongly recommend that South Korea readily go to call for coalition forces to counter North Korea's further aggression. The justification for

the planning is sufficiently gained by the various underway UN sanctions.

South Korea would ask neighboring countries to join in the first place,and other volunteers as well. With the overwhelming multi-national forces, South Korea may appeal to the complete removal of North Korea's WMDs at first hand, but it may also request the help to remove

the totalitarian dictatorship, appealing humanitarian purposes.

In conclusion, it is timely and appropriate for South Korea to step ahead of gaining a turning point to resolve security problems, especially in crisis situations.